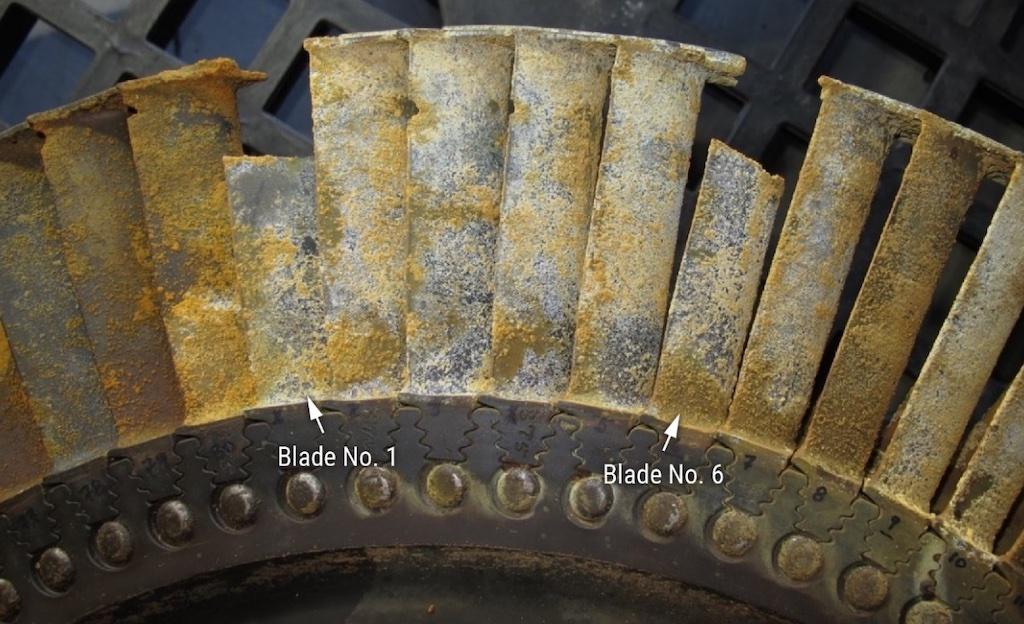

The turbine section of the No. 2 engine was damaged and degraded.

The NTSB found the probable cause of the July 2, 2021, crash of the Transair Boeing 737 freighter was: “the flight crewmembers’ misidentification of the damaged engine (after leveling off the airplane and reducing thrust) and their use of only the damaged engine for thrust during the remainder of the flight, resulting in an unintentional descent and forced ditching in the Pacific Ocean. Contributing to the accident were the flight crew’s ineffective crew resource management, high workload, and stress.”

The turbine section of the Number 2 engine was damaged and degraded, but the crew failed to recognize this. The captain was unaware of the first officer’s thrust changes because he was busy trying to talk to the controller about the emergency. He had been criticized by Transair’s chief pilot for returning to the airport without completing the required abnormal checklist, and that kept him from making an immediate return to the airport.

The first officer (FO) independently moved the left and then the right thrust lever aft, contrary to his training. The crew did not perform key steps of the checklist, including identifying, confirming, and shutting down the affected (right) engine.

The crew experienced task overload due to stress, which can degrade cognitive functions such as working memory, attention, and reasoning. The Engine Failure and Shutdown checklist assumed the airplane had asymmetric thrust, which was not the case. The checklist did not consider the possibility that a flight crew might need to delay its execution until the failed engine was identified. If the checklist had been started earlier in the accident sequence, both crewmembers might have recalled their earlier correct diagnosis of the affected engine.

As the airplane’s descending flight path became increasingly harrowing, the pilots experienced stress-related attentional narrowing and rigid thinking, and they failed to reconsider use of the left engine. Finally, crew resource management (CRM) was inadequate. The captain gave attention to lower-priority tasks and did not ensure that the Engine Failure checklist was properly accomplished.

When asked by NTSB investigators why he just accepted the FO’s judgment about which engine had failed, the captain said the first officer “never makes a mistake.” He trusted the FO and did not verify which engine had actually failed.

Aviation’s Historical Themes

Several old themes from the history of aviation come to mind. The first is to see at least two indications before shutting down an engine. If the crew had turned up the engine instrument integral and flood lighting and looked closely at oil pressure, oil temperature, N1 and N2 RPM and EGT, they would have realized the left engine was running and was merely in idle.

The second theme is “aviate, navigate, and communicate,” in that order. Don’t lose control of the airplane or miss an important cue while you’re talking.

The third theme is “maintain aircraft control, assess the situation, and take proper action.” The FO’s initial level off altitude and airspeed control was poor. He could have engaged the autopilot to deal with those issues. Since the pilots never properly assessed the situation, their subsequent actions were misguided and resulted in loss of the airplane.

The difficulty of Transair Flight 810’s situation should not be underestimated. An ambiguous engine failure just after takeoff in a climbing turn over the ocean at night is one of the toughest scenarios you could have. The pilots missed their chance to save the airplane, but they lived to fly another day. They learned a valuable lesson, and so have other pilots who know what happened.

In An Emergency, Trust But Verify, Part 1, https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/emerge…

In An Emergency, Trust But Verify, Part 2: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/emerge…