This article is published in Air Transport World, part of Aviation Week Intelligence Network (AWIN), and is complimentary through May 17, 2024. For information on becoming an AWIN Member to access more content like this, click here.

In 2012 Africa’s aviation ministers saw a “compelling need” to do something about aviation safety. Their answer was the Abuja Safety Targets. Over a decade later, overall implementation stands at just 46%.

However, experts say this percentage masks genuine progress, and that a more pragmatic approach is helping accelerate change.

When the safety targets were established, Africa topped the world leaderboard for fatal air accidents, and many of the continent’s airlines were banned by the European Union.

“That was a trigger for us to say, ‘Come on, guys, what is going on? We need to take ownership of this ourselves, as Africans. We can’t wait for the Europeans to ban us,’” said Airlines Association of Southern Africa (AASA) CEO Aaron Munetsi, who was working for South African Airways (SAA) at the time.

In response, aviation ministers from 35 African countries, along with representatives from EASA, IATA and ICAO, gathered for a safety conference in Abuja, Nigeria, which ultimately led to the 2012 Abuja Declaration and the Abuja Safety Targets.

“Anyone and everyone who was involved in aviation safety was called into that room,” Munetsi said. “At that time, I think 25 countries—almost half the countries on the continent—were on the EU banned list. This was simply an indication that we were not doing enough oversight.”

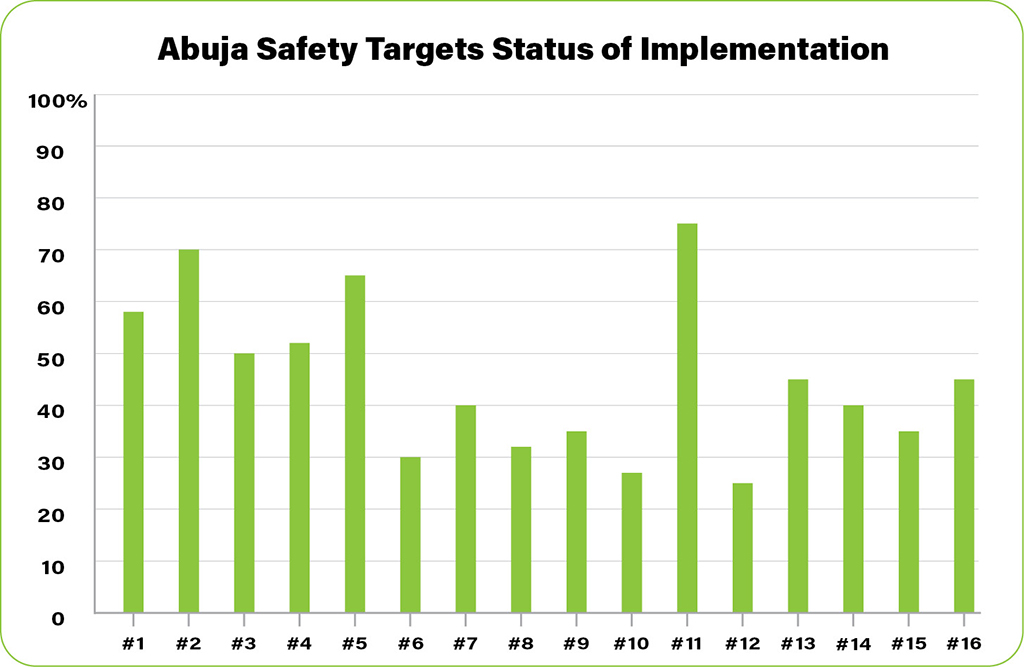

The 12 original Abuja Safety Targets sought to tackle critical issues, such as reducing accident rates, remedying significant safety concerns, creating autonomous civil aviation authorities (CAA), complying with basic ICAO safety standards, certifying international airports, and increasing the rollout of IATA Operational Safety Audits (IOSA). Four more objectives—covering air navigation services—were added in 2017.

“I would say the Abuja standards are the bedrock for anything that we do,” Munetsi said.

The African Civil Aviation Commission (AFCAC) was tasked with monitoring implementation of the Abuja Safety Targets, in close partnership with ICAO. AFCAC is the body that handles aviation affairs for the African Union (AU), which comprises 55 states.

“For anything to do with [African] aviation safety and security, ICAO will never do anything without the involvement of AFCAC. And AFCAC will never do anything without the involvement of ICAO,” Munetsi said.

But where do things stand now with the targets? “Status of implementation has risen gradually over the years, up to an average of 46% for all states in July 2023,” AFCAC told ATW. “Some individual member states have met some of the targets. However, as a group average (54 states), none of the targets have been met.”

While 46% sounds low, this marks an improvement from 35% compliance in 2018. However, Munetsi said implementation of around 60% was originally seen as “the very basic bare minimum,” covering aspects of safety that were “nonnegotiable.” Ethiopia, Kenya and South Africa are “getting quite ahead of the program,” Munetsi said, while others are lagging.

Given the diversity of countries involved, the low overall implementation figure masks credible progress. For example, 29 of 48 member states of the ICAO Regional Aviation Safety Group for Africa-Indian Ocean met the original 60% compliance target, and 11 have now exceeded 75% implementation of ICAO’s Global Aviation Safety Plan. All 22 significant safety concerns identified in 2012 have now been addressed, and the rollout of independent CAAs (Target 2) is 70% complete.

Notably, there were no controlled flight into terrain or loss-of-control inflight incidents in 2022, but the accident rate remains elevated because of runway-related shortcomings.

“Runway excursion-related accidents remained the most predominant high-risk category of occurrence, and continues to be the main priority,” African Airlines Association (AFRAA) secretary general Abderahmane Berthé said. AFRAA is a lobbying group representing 54 African airlines.

Moreover, the November 2023 update to the EU Air Safety List shows that airlines from 12 African countries are currently banned by the EU over safety concerns—down by half since the targets were conceived, indicating improved safety oversight.

Reflecting on progress to date, AFCAC told ATW that the rollout of performance-based navigation (Target 11) has moved more quickly than expected, reaching 75% compliance. However, the air navigation targets are “generally lagging behind” because of the substantial cost of replacing older equipment. Money has also been a barrier for the certification of international airports, because many need upgrades. AFCAC is working to secure additional funding from international partners.

The next steps include realignment of the safety targets to the ICAO Global Aviation Safety Plan and Global Air Navigation Plan “to ensure that they remain current, relevant and achievable for member states,” AFCAC said. This realignment process began in 2022, and is expected to be completed by the end of Q1 2024.

AASA’s Munetsi said the current goal is not to reach minimum Abuja compliance, but instead for countries to get several percentage points beyond that. He reasons that once safety systems, processes and procedures have been implemented, the risk of countries slipping below the minimum threshold in future will be reduced. But how will Africa get to that level?

Part of the answer lies in a more hands-on approach, using active cooperation between the three main airline associations—AASA, AFRAA and IATA—and the various regulatory oversight bodies, including AFCAC, ICAO and national CAAs.

In early 2024, AFCAC hosted a Joint Prioritized Action Plan meeting to check in with African states on their progress, and see what assistance might be needed. One area that is gaining traction is peer support, where states actively help one another. Munetsi gave the example of South Africa, which scored 92% in its 2023 ICAO safety audit. South Africa is now offering to mentor other African countries, facilitated by AFCAC, IATA and ICAO.

“It’s easier for these countries to go state-to-state to ask for help,” Munetsi said. “If we say ‘go to IATA or ICAO,’ two things happen. The first is it’s almost like they are reporting themselves, saying they are not performing well, and they don’t want to look bad. The second thing is when ICAO or IATA come in, they come at a cost, and that becomes a deterrent.”

Conversely, South Africa might be willing to send a team, with the receiving country only having to cover travel and subsistence costs. “Already we are seeing some countries reaching out to South Africa,” Munetsi said.

FOCUS AFRICA

IATA is aware of these challenges, and has responded with the Focus Africa program, which launched in 2023. One of Focus Africa’s six core areas is safety, and IATA has established a Collaborative Aviation Safety Improvement Program (CASIP) to move things forward. CASIP participants include AFCAC, Airbus, Boeing, ICAO, US FAA and the African airline bodies. An initial CASIP meeting was held in October 2023 and a work program for the group is now being finalized.

“Rather than this being driven by ICAO, or the states, it was actually driven by the needs of our member airlines,” IATA Africa & Middle East regional director for operations, safety & security Sharron Caunt said. “One of the things that we do in Africa is we set superb aspirational goals. But then what’s the mechanism to actually implement the change?”

Safety target implementation is measured at the state level, but airlines have a key part to play.

“You have to have the industry and states working together. Because otherwise, you wouldn’t be able to prioritize the issues,” Caunt said. “Part of the CASIP program is to actually roll our sleeves up, go in there and actually deliver activities.”

This involves frank roundtable discussions, speaking with airlines and states about what the real issues are, and then brainstorming solutions, such as training and capacity building.

IATA also held a three-day runway safety meeting with one African state, which ended with a “FOD plod” along the airport’s runway and taxiways, collecting foreign object debris—or litter—that could be ingested into aircraft engines.

“Everybody was so excited because they were actually part of the change that we’re making,” Caunt said. “We saw the immediate change.”

Caunt’s own aviation career began in ground operations, so she sees value in raising safety awareness among hands-on staff, as well as at the aeropolitical level.

MAKING SAFETY ACCESSIBLE

While IATA initiatives like Focus Africa are helpful to larger airlines, many smaller operators are not IATA members.

“In my region, which is south of the Sahara, there are approximately 23 IATA carriers, but there are hundreds and hundreds of small operators who don’t have IATA to turn to,” Tom Kok, director at African safety specialist AviAssist Foundation, told ATW.

AviAssist has tracked the Abuja Safety Targets since their creation, and Kok believes they have helped the industry focus on core safety priorities. However, the high-level objectives, which include cutting the number of runway excursions, are aimed at CAAs, rather than aviation workers performing their day-to-day duties.

Mirroring IATA’s hands-on approach, Kok believes it is important to translate the Abuja Safety Targets into practical actions.

“A lot of them don’t mean much to the average safety person in a smaller operator in Africa,” he said. “That’s something we suffer from in safety overall. Amongst ourselves, we understand what we say, and we think it’s all very important. But people—whose support we need—fall asleep when we show them an IATA or ICAO document. We need to translate our very technical and often boring messages into something that people can relate to.”

He argues that African safety needs to be rebranded, making it more relevant to grassroots people—and to senior government officials whose buy-in is needed for critical investments.

“If we preach about ICAO Annex 17, the minister of finance will say ‘I don’t get how that relates to my work.’ We’re very good at technical innovations, like better runway lights, radar or whatever, but not so much in innovating our approach to humans,” Kok said. “The Abuja Targets themselves are good, but the way we work with them is still very formal. We go to a meeting in Entebbe and we talk about the status of the Abuja Targets, but we don’t give any tools.”

AviAssist uses cartoons and nontechnical language to strengthen its aviation safety messages, making them more accessible. Kok is also keen to maximize the potential of online training, which gained greater acceptance during the pandemic. He argues that smaller operators cannot afford to send their staff to Montreal for safety training, and even if they could, the language may be too technical. Online training offers another way to lower the barriers to safety awareness.

“I’m thinking maybe the 17th Abuja Target should be to make the Abuja Targets more understandable for the rest of Africa,” Kok said.